Repeal state public health emergency, emergency management, and communicable disease control laws.

American Domestic Bioterrorism Program

Tools for dismantling kill box anti-law

Repeal of state public health emergency laws (PDF)

How to draft a bill for a state legislature to repeal state-level emergency management, public health emergency, and communicable disease control laws.

Contents:

Note about intended users

Synopsis: Model State Emergency Health Powers Act (MSEHPA)

Steps for state legislators and governors to repeal public health emergency laws

Sample repeal bill

Note about intended users

This how-to guide is intended for readers who have read and understood the documentary evidence base for three premises:

Global pandemics of deadly communicable disease pathogens are not possible, whether the allegedly highly-transmissible and highly-virulent pathogen is natural or lab-manipulated.

Global pandemics of deadly communicable disease can and have been simulated, using laws (communicable disease control law, public health emergency law); local, self-limiting dispersal of biologically-active poisons; falsified/manipulated diagnostic, medical coding and epidemiological data; and mass media propaganda.

Public health emergency law is part of a mass-deception program used to generate public fear, facilitate biodefense racketeering, promote compliance with economic and military-pharmaceutical homicide programs, and shorten human lives.

Supporting the conclusions:

Public health emergency law is about centralizing political power to legalize crime, and lawmakers who understand and object to the legalization of crime have sound moral and legal reasons to repeal public health emergency and communicable disease control laws, and shut down public health, emergency management and communicable disease control programs.

If you do not yet understand the evidence, and would like more information, please see legal and regulatory analysis by Katherine Watt and Sasha Latypova.

Synopsis: Model State Emergency Health Powers Act (MSEHPA)

Emergency-predicated centralization of government authority within the federal executive branch has a long history in the United States.

Examples of Congressional acts signed by US Presidents to consolidate executive power in response to circumstances construed as national emergencies include the Trading with the Enemy Act (1917), Emergency Banking Act (1933), Reorganization Act (1939), Public Health Service Act (1944), War Powers Resolution (1973), National Emergencies Act (1976), Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (1988), PATRIOT Act (2001), Agricultural Bioterrorism Protection Act (2002), Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act (2002), Homeland Security Act (2002).

Executive legislation has also been enacted to expand executive emergency power, taking the form of executive orders and agency regulations published in the Federal Register.

Many US states have also enacted state-level general emergency management laws, mostly during and since the 1970s.

In 2001, public health lawyers affiliated with Johns Hopkins University, Georgetown University and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) published a Model State Emergency Health Powers Act (MSEHPA).

The MSEHPA was drafted to further override constitutional separation of powers and centralize state-level executive authority on public health emergency predicates, including communicable disease outbreaks. The ensuing lobbying campaign drew momentum from false-flag anthrax attacks in September 2001.

Several related model acts are in circulation, including the Model State Public Health Privacy Act (1999); Model State Public Health Act (MSPHA, 2003) and Uniform Emergency Volunteer Health Practitioners Act (UEVHPA, 2007), and Model Public Health Emergency Authority Act (MPHEAA, 2023).

These model acts, combined with deception campaigns providing false information to federal and state lawmakers and the public about biological threats, biodefense, biosecurity, bioterrorism, emerging infectious diseases and related topics, have been used to lobby state lawmakers to expand government authority to apprehend, detain, injure and kill people and seize private property during declared public health emergencies.

Since 2001, state legislatures and governors have updated and amended state legal codes to enact many provisions of the MSEHPA.

MSEHPA:

“The Model Act is structured to reflect 5 basic public health functions to be facilitated by law:

(1) preparedness, comprehensive planning for a public health emergency;

(2) surveillance, measures to detect and track public health emergencies;

(3) management of property, ensuring adequate availability of vaccines, pharmaceuticals, and hospitals, as well as providing power to abate hazards to the public's health;

(4) protection of persons, powers to compel vaccination, testing, treatment, isolation, and quarantine when clearly necessary; and

(5) communication, providing clear and authoritative information to the public.”

Since January 2020, federal and state public health, military and law enforcement officials have demonstrably used federal and state public health emergency laws to commit acts of fraud, extortion, theft, torture, homicide, and other crimes, by characterizing Covid-19 as a global pandemic of a life-threatening communicable disease, and by characterizing criminal acts as components of a lawful, coordinated, necessary, life-saving, government emergency response program.

Under existing federal and state laws, fraudulent, non-validated government claims about the existence, transmissibility and virulence of communicable disease pathogens form the legal basis for government declarations, determinations, executive orders, expenditures, policies and programs.

Under existing federal and state laws, fraudulent, non-validated diagnostic tests form the legal basis for government acts to classify, apprehend, detain and treat tested persons as public health threats, as 'asymptomatic,' 'precommunicable,' or symptomatic carriers of non-validated communicable disease pathogens.

Note: Presidential Executive Order 13295, as amended by EO 13375, 13674 and 14047, currently in force under 42 USC 264, classifies non-specific respiratory diseases as "quarantinable" diseases, including "Severe acute respiratory syndromes, which are diseases that are associated with fever and signs and symptoms of pneumonia or other respiratory illness, are capable of being transmitted from person to person, and that either are causing, or have the potential to cause, a pandemic, or, upon infection, are highly likely to cause mortality or serious morbidity if not properly controlled" and "influenza caused by novel or reemergent influenza viruses that are causing, or have the potential to cause, a pandemic."

Under existing federal and state laws, fraudulent, non-validated data about the safety, efficacy, purity, potency and sterility of drugs, devices and biological products form the legal basis for government officials to contract with pharmaceutical companies to develop, manufacture, purchase and deploy emergency "medical countermeasures" used to intentionally injure and kill recipients.

Federal and state government acts legalized by public health emergency laws include but are not limited to issuance of public health emergency declarations, determinations and executive orders; establishment of fraudulent diagnostic testing programs and epidemiological 'dashboards;' imposition of school and business occupancy limitations and closures; mask mandates; hospital homicide protocols (sedation, dehydration and starvation); and military-pharmaceutical homicide protocols (vaccine mandates).

Public health law, and especially civil and criminal liability exemptions under the Defense Production Act (1950), "Good Samaritan" laws, National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act (1986), and the PREP Act (2005), have given public health and military officials; manufacturers and regulators of biological products, drugs and devices; pharmacists, nurses, doctors, school administrators, public and private employers and other individuals, license to kill.

Steps for state legislators and governors to repeal public health emergency laws

If you are a state lawmaker interested in repealing your state's crime-enabling public health emergency laws, or a citizen interested in lobbying your state lawmakers to repeal crime-enabling public health emergency laws, the following information may be useful.

STEP 1 - Identify public health emergency laws enacted by your state legislature and governor.

Several organizations collect this data, including Network for Public Health Law, Temple University Center for Public Health Law Research, and National Conference of State Legislatures.

For example, the Network for Public Health Law produced a table in 2012, summarizing some of the state-level public health emergency laws that had been enacted through 2011.

Column headers referred to sections of the 2001 Model State Emergency Health Powers Act:

§ 104(m) - Defines public health emergency or like term.

§ 301 - Public health emergency reporting

§ 401 - Public health emergency declaration

§ 404(a)(1) - Suspension of laws

§ 502 - Access/control of facilities and properties

§ 603 - Vaccination/Treatment

§ 604, 605 - Isolation & Quarantine

§ 608 - Licensing of health care workers

§ 804 - Immunity for state/private actors.

For example, some of the Texas state laws identified in the 2012 table include:

§104(m) - Texas Codes Annotated §81.003(7). Defines "public health disaster" and "public health emergency."

§301 - T.C.A. §81.041(f) - Authorizes state health commissioner, "in a public health disaster," to "require reports of communicable diseases or other health conditions from providers."

§401 - T.C.A. § 81.003(7)(a) - Defines "public health emergency" as a "determination" issued by commissioner, in the form of an "emergency order."

§401 - T.C.A. 81.082(d) - Authorizes commissioner to renew "public health emergency orders" in 30-day increments.

§502 - T.C.A. 81.082(c-1) - Authorizes commissioner to designate health care facilities "capable of providing services for the examination, observation, quarantine, isolation, treatment or imposition of control measures."

§603 - T.C.A. § 81.085(i) - Authorizes commissioner to "impose an area quarantine coextensive with the area affected" by a communicable disease outbreak; authorizes health department officers to demand individuals disclose "immunization status;" and authorizes law enforcement officers to "use reasonable force to secure a quarantine area and...prevent an individual from entering or leaving the quarantine area."

STEP 2 - Locate the online database for your state's laws and identify the public health emergency, emergency management and communicable disease control sections.

Titles of the laws vary from state to state.

You may find public health emergency law under titles such as:

Public Health Emergency Response Authority

Public Health Disaster

State Public Health Emergency

Public Health Emergencies

Emergency Management

Emergency Management and Security

Emergency Services Act

Military Affairs and Civil Defense

Militia and Military Affairs

Law Enforcement, Emergency Management and Military Affairs

Military, Emergency Management and Veterans Affairs

Disaster Preparedness Act

State Disaster Preparedness Act

Homeland Security Act

Control of Diseases of Public Health Importance

Disease Control and Threats to Public Health

Prevention of Spread of Communicable Diseases

Quarantine and Isolation

Reporting requirements for infectious or contagious diseases and conditions

Good Samaritan Act

Limitation on liability for medical care or assistance in emergency situations

In Texas, for example, T.C.A. § 81 is located in the Texas Health and Safety Code, under Title 2, Health, Subtitle D, Prevention, Control, and Reports of Diseases; Public Health Disasters and Emergencies, at Chapter 81.

Chapter 81 is titled "Communicable Diseases; Public Health Disasters; Public Health Emergencies"

Texas Health and Safety Code, Chapter 81 was enacted in 1989 as the "Communicable Disease Prevention and Control Act." It has been amended and expanded by Texas legislators and governors in 1991, 1997, 1999, 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013, 2015, 2017, 2019, 2021 and 2023.

You can find related laws by reading.

For example, Texas Health and Safety Code §81.009(a) recognizes "exemption from medical treatment," and authorizes detention and isolation of an individual who declines treatment. §81.009(b) revokes recognition of the right to be "exempt from medical treatment," stating it "does not apply during an emergency or an area quarantine or after the issuance by the governor of an executive order or a proclamation under Chapter 418, Government Code (Texas Disaster Act of 1975)."

Chapter 418 is titled "Emergency Management" and is located in the Texas Government Code, Title 4, Executive Branch, Subtitle B, Law Enforcement and Public Protection.

Texas Government Code Chapter 418 was first enacted in 1975 as the "Texas Disaster Act" and has been amended and expanded in 1987, 1995, 1997, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013, 2019, 2021 and 2023.

Continue your legal research until you've located all the state laws addressing communicable disease control, public health emergencies, and emergency management in your state.

NOTE: The Texas example provided above, and used for the sample repeal act below, is not a complete list of all relevant Texas laws that should be repealed. It's a demonstration of how the investigation process starts, intended to help readers conduct legal research in their own states.

STEP 3 - Draft a repeal bill and provide it to your state lawmakers.

If:

(1) You understand how state public health emergency laws have already been used to injure, kill and steal from the people of your state, because you have seen those laws invoked and applied since January 2020, and

(2) You don't want your governor or state health officials to exercise existing legal authority to extend Covid-19 emergency policies and programs further, and you don't want your governor or state health officials to declare additional public health or other emergencies in the future; exercise legal authority to deploy state and local public health and law enforcement officers and federal military officers (National Guard); expel you and your children from schools, businesses, workplaces and public facilities; enforce masking, social distancing, occupancy and medical treatment mandates; and apprehend, detain, assault, torture and kill people on false, non-validated and impossible-to-validate premises

Then:

(1) Draft a short bill (sample below) and give it to state lawmakers in your state who can repeal the relevant laws.

(2) Help your state lawmakers understand the lies that they and their predecessors have been told, which led to the passage of the state public health emergency, communicable disease control, and emergency management laws.

(3) Urge your state lawmakers to repeal the public health emergency, communicable disease control, and emergency management laws.

Sample repeal bill

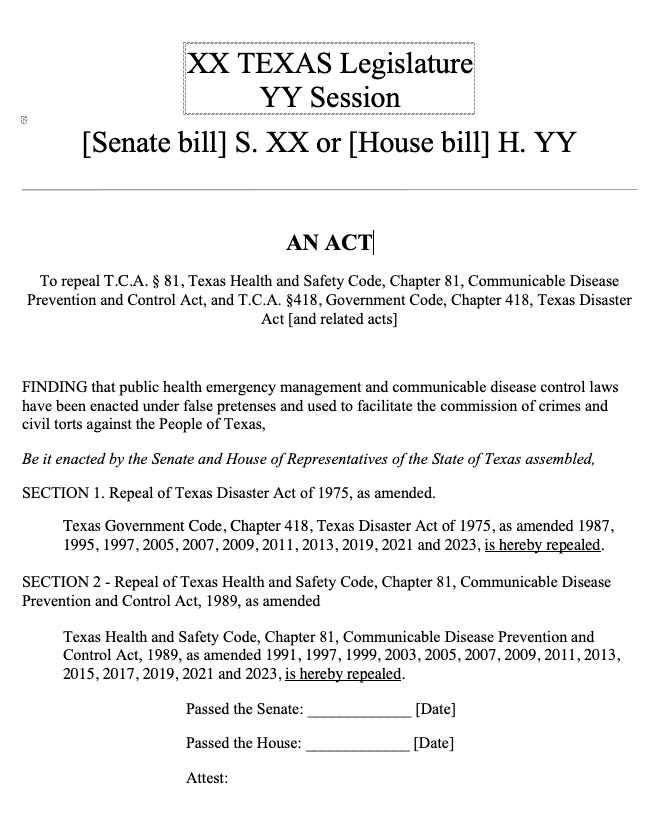

XX TEXAS Legislature

YY Session

[Senate bill] S. XX or [House bill] H. YY

AN ACT to repeal T.C.A. § 81, Texas Health and Safety Code, Chapter 81, "Communicable Disease Prevention and Control Act," and T.C.A. §418, Government Code, Chapter 418, "Texas Disaster Act" [and related acts]

FINDING that public health emergency management and communicable disease control laws have been enacted under false pretenses and used to facilitate the commission of crimes and civil torts against the People of Texas,

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the State of Texas assembled,

SECTION 1. Repeal of Texas Disaster Act of 1975, as amended.

Texas Government Code, Chapter 418 "Texas Disaster Act of 1975," as amended 1987, 1995, 1997, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013, 2019, 2021 and 2023, is hereby repealed.

SECTION 2 - Repeal of Texas Health and Safety Code, Communicable Disease Prevention and Control Act, 1989, as amended

Texas Health and Safety Code, Communicable Disease Prevention and Control Act, 1989, as amended 1991, 1997, 1999, 2003, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013, 2015, 2017, 2019, 2021 and 2023, is hereby repealed.

Passed the Senate: _____________ [Date]

Passed the House: _____________ [Date]

Attest:

Related Bailiwick reporting and analysis

Nov. 23, 2023 - Opportunities for US state lawmakers to shield their populations from the next 'public health emergency'-predicated federal assaults.

Jan. 20, 2024 - On the historical development and current list of ‘quarantinable communicable disease.