Pathogen Access and Benefits Sharing

The insane reality is that these negotiations are essentially a trade dispute over WHO should "benefit" from the next "pathogen with pandemic potential." Get the facts and help #StopTheTreaty.

Updated: March 1, 2024

StopTheTreaty.org #StopTheTreaty

If you really want to know what is holding up the negotiations for the Framework Convention for Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Tesponse, then you must comprehend the disagreements regarding the proposed PABS System.

Global Call for An Equitable Pathogens Access and Benefit-Sharing System in the Pandemic Instrument

The Intergovernmental Negotiating Body held meetings to negotiate the proposed “Pandemic Treaty” from February 19 to March 1, 2024.

Please watch the videos below…

The Third World Network has published the following articles:

March 1, 2024

Developing countries call for deliverable provisions on access and benefit sharing, equity in pandemic instrument

https://www.twn.my/title2/health.info/2024/hi240301.htm

February 29, 2024

WHO: Developed countries dilute effectiveness and accountability in PABS proposal

https://www.twn.my/title2/biotk/2024/btk240201.htm

February 28, 2024

Some Intellectual Property Claims Related to Pathogens That Can Cause Public Health Emergencies

https://www.twn.my/title2/intellectual_property/info.service/2024/ip240201.htm

February 28, 2024

Global Call for An Equitable Pathogens Access and Benefit-Sharing System

https://www.twn.my/title2/intellectual_property/info.service/2024/ip240202.htm

February 18, 2024

WHO: Attempts to side-line Africa and Equity Group proposal on the PABS System

https://www.twn.my/title2/health.info/2024/hi240205.htm

https://odysee.com/@DaisyPapp:a/James-Roguski.02.17.2024fullI.nterview:8

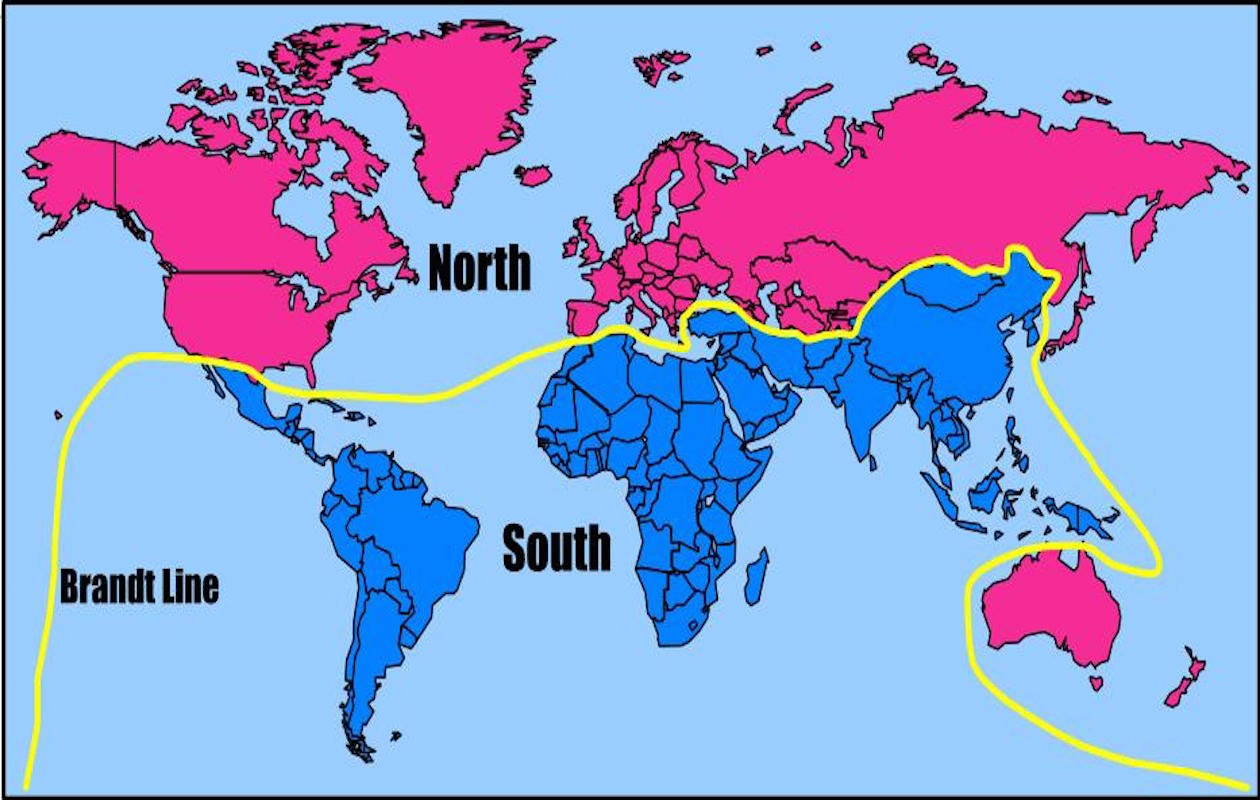

The Intergovernmental Negotiating Body and the WHO are hoping to promise TENS OF BILLIONS OF DOLLARS to the Pharmaceutical Hospital Emergency Industrial Complex and the nations of the Global South in order to get them to agree to a “Pandemic Agreement” by the end of May 2024.

It is highly unlikely that they will reveal how much all of this is going to cost. They plan to discuss that after they attempt to adopt the agreement.

Delegates from nations in the “Global North” are demanding protection of intellectual property rights and corporate profits at the expense of people’s health.

Delegates from nations in the “Global North” are demanding equitable access to “pandemic-response products” that do NOT stop infection and do NOT stop transmission but DO cause immune dysfunctions that lead to a wide range of diseases as well as sudden and excess deaths.

These people are either insane, evil or both.

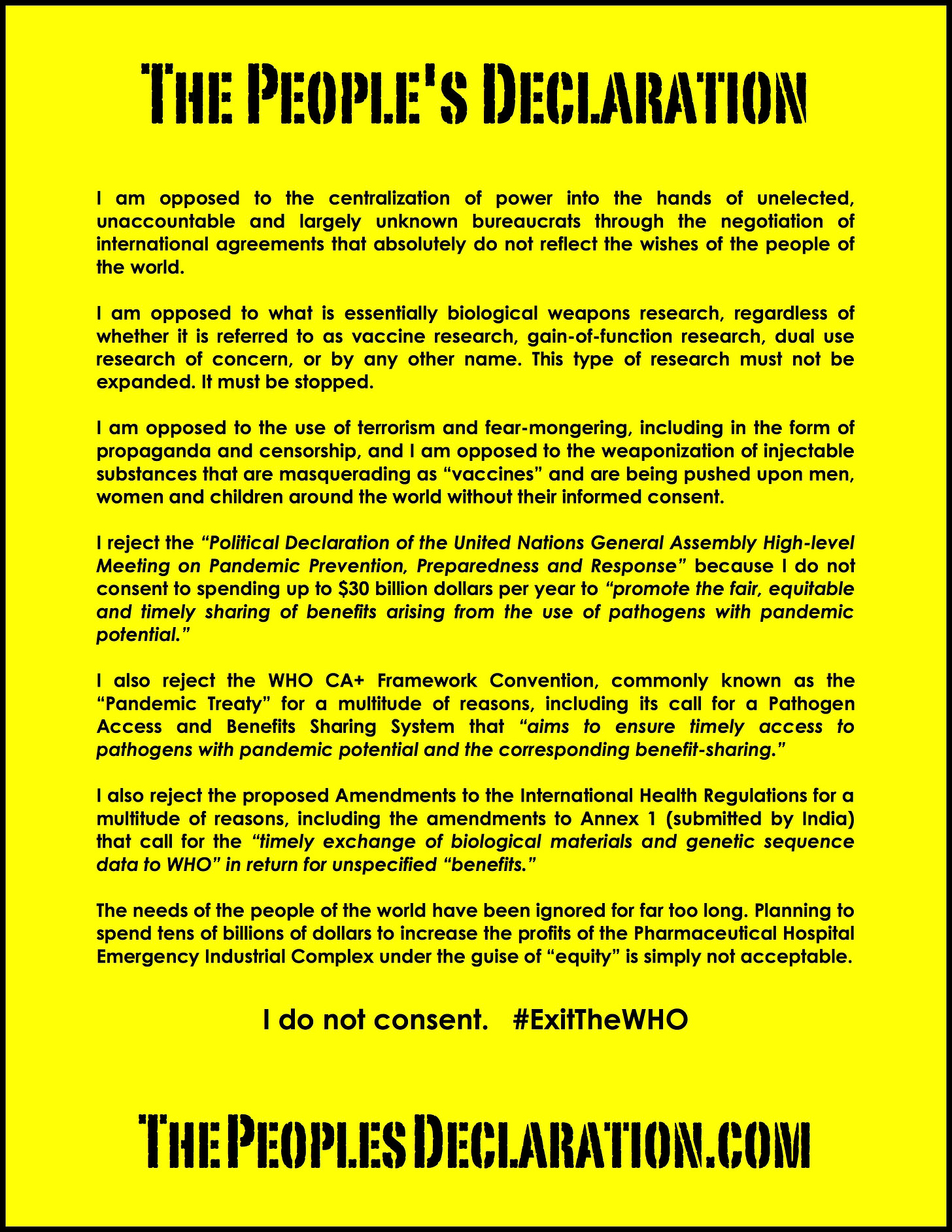

Click on the image above to download it to your computer or phone so that you can share it across social media. Download the PDF below in order to print the flyer and distribute it far and wide.

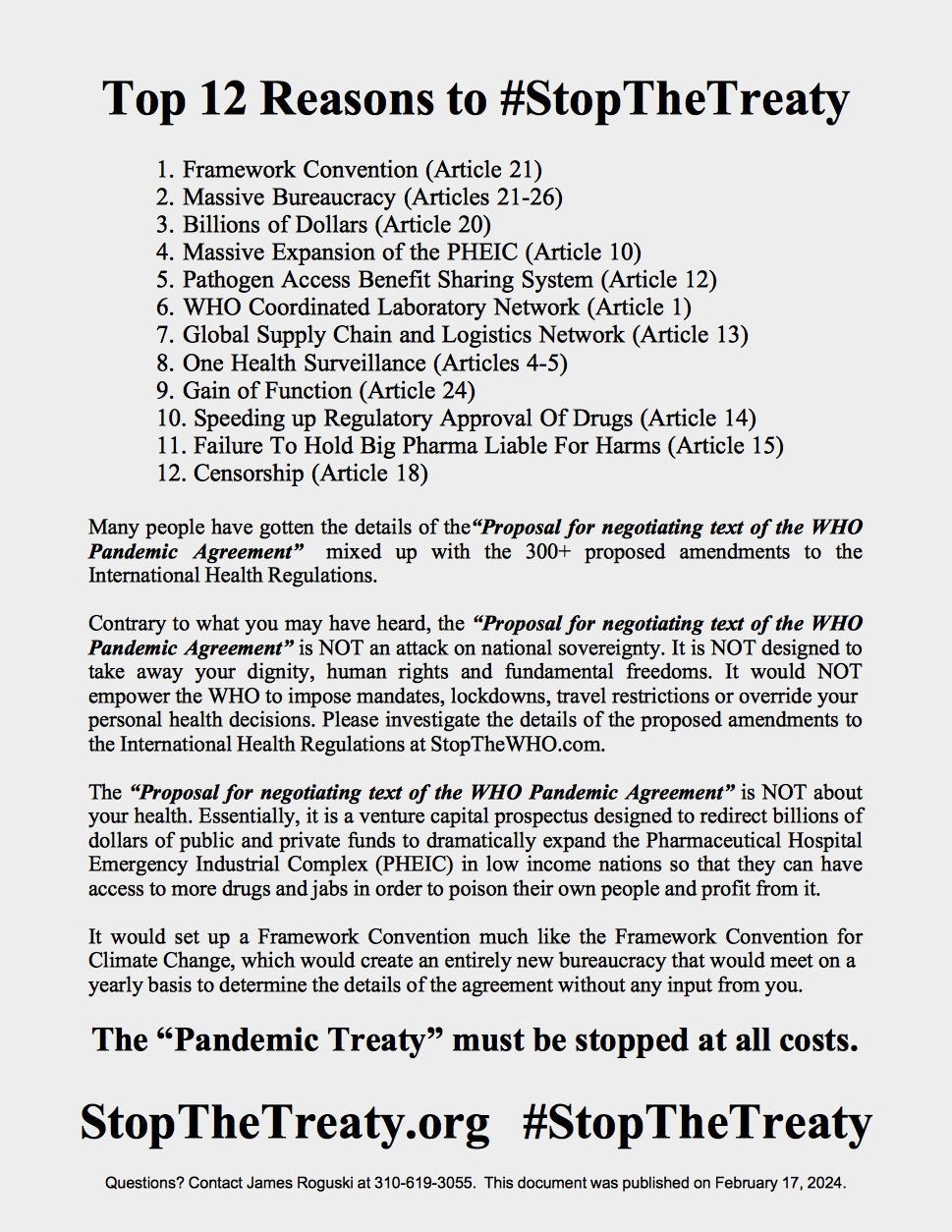

Click on the image above to download it to your computer or phone so that you can share it across social media. Download the PDF below in order to print the flyer and distribute it far and wide.

The World Health Assembly consists of 194 sovereign member nations. In order for a new “Pandemic Agreement” to be adopted, a 2/3 majority is needed, which amounts to 130 votes.

There are 70+ nations combined in the WHO’s African Region and the “Group for Equity.” They have proposed a comprehensive Pathogen Access and Benefit Sharing system and they are unhappy that their proposals have not been accepted.

This block of 70+ nations is more than the 1/3 needed to ensure that no agreement can be reached without their cooperation.

BELOW ARE SOME EXCERPTS FROM A RECENT ARTICLE BY JACOBIN.COM

The existing International Health Regulations — which date back to 1969 and were last revised in 2005 — are already legally binding. Yet this did nothing to prevent hoarding of vaccines and other pandemic countermeasures during COVID-19. The regulations also stipulate that in return for sharing genetic information, countries are not to be slapped with travel or trade restrictions, yet this legal requirement was one of the first of many to be ignored in 2020.

In the talks, there are many lines of disagreement between developed and developing nations, but the main point of contention lies with the quid pro quo at the heart of the negotiating text — the proposed access-and-benefit mechanism, formally titled the WHO Pathogen Access and Benefit-Sharing System (WHO PABS System).

In return for Global South knowledge sharing, the Global North is supposed to commit to help finance monitoring in these poorer regions, and to provide universal access to the medical fruits of such monitoring: vaccines and therapeutics.

Moreover, when COVID-19 hit, developing countries freely shared sampling data on the expectation of receiving the benefits of such sharing under existing frameworks, but never did.

In the negotiating text, in the event of another pandemic, the PABS System would see 20 percent of the production of medical countermeasures donated to the WHO to be distributed on the basis of need. Civil society development and public health organizations have, understandably, criticized this as woefully insufficient.

But for pharmaceutical companies, even 20 percent is too much. In response to the release of the negotiating text last October, the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA) denounced it.

The People’s Vaccine Alliance, a coalition of over one hundred development and health NGOs, trade unions, and human rights campaign groups, notes that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the twenty biggest pharmaceutical giants spent almost as much on payouts to shareholders and executives as they did on research and development. Between 2020 and 2022, these firms spent $377.6 billion on such largesse and $414.6 billion on R&D.

A clear case of corporate greed and Big Pharma’s capture of the diplomatic force of Western governments, it would appear.

https://jacobin.com/2024/02/pandemic-treaty-intellectual-property-big-pharma

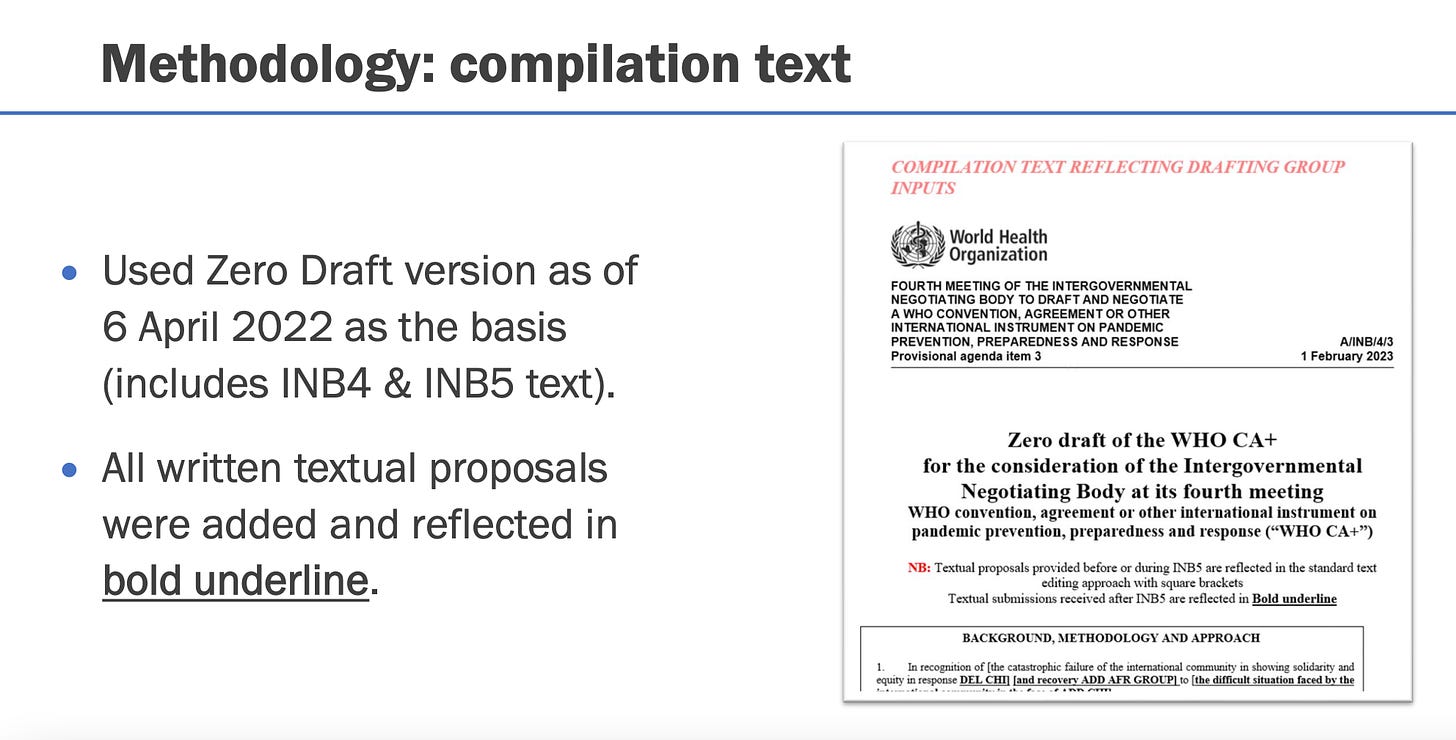

At the current moment, an official draft for Article 12 is NOT available. Competing proposals and a number of opinions are provided below.

BELOW ARE SOME EXCERPTS FROM A RECENT ARTICLE BY HEALTHPOLICH-WATCH.NEWS

Annual ‘PABS subscription’ proposal

Instead of a new draft, there is a PABS proposal from the sub-committee that conducted inter-sessional discussions on Article 12 that offers an advance on the previous pandemic agreement draft.

According to the proposal, shared with stakeholders at the start of the INB’s eighth meeting on Monday, commercial manufacturers that are producing vaccines, therapeutic or diagnostic products for “pathogens with pandemic potential” should pay an annual fee (related to their size) “to support the PABS system and strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness and response capacities in countries”.

They should also make in-kind contributions such as tech transfer and know how. During a public health emergency with pandemic potential or a pandemic, they should make “real time contributions of relevant diagnostics, therapeutics and/or vaccines”, including a percentage free and not-for-profit prices to be made available upon request by WHO and delivered, through mechanisms set out in Article 13, which deals with a global supply chain.

However, countries will be obliged to immediately share genomic sequencing data (GSD) and biological material of dangerous pathogens with laboratories and bio-repositories participating in WHO-Coordinated Lab Networks (CLNs) and on WHO-recommended sequence databases (SDBs).

“Intellectual property rights may not be sought on biological materials and GSD provided to the CLNs and SDBs,” according to the proposal.

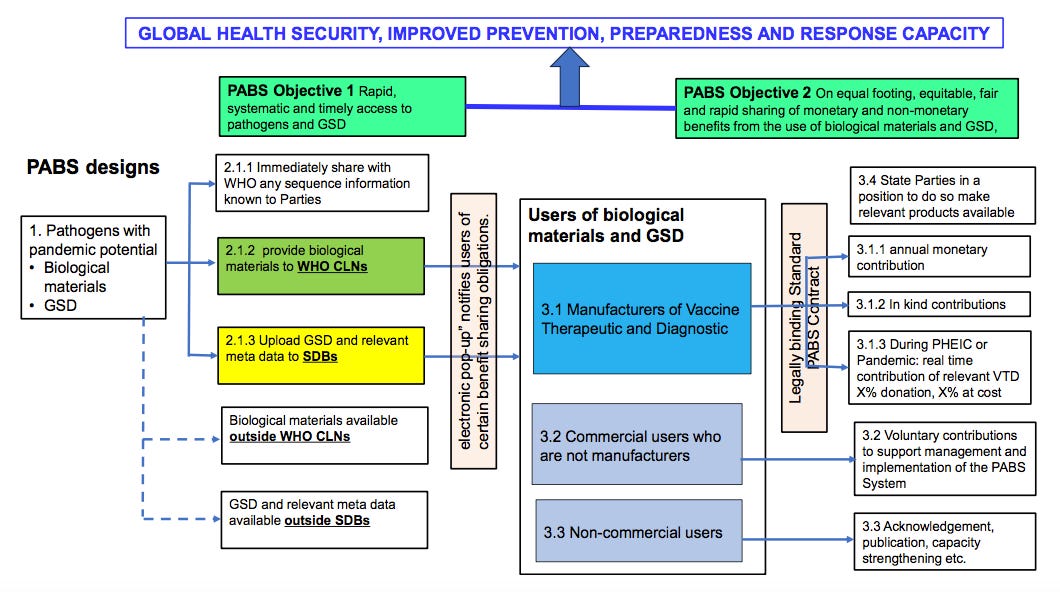

BELOW ARE THE PABS DESIGN ELEMENTS THAT WERE PROPOSED BY THE VICE CHAIR AND CO-FACILITATORS

Article 12: Vice Chair and Co-Facilitators’ proposed PABS design elements

14 February 2024

Background

The proposed design elements were discussed in informal consultations and two subgroup meetings on 31 January and 1 February 2024. This version was revised based on comments and suggestions from the two subgroup meetings. This version was discussed at length with information from experts in the area of GSD databases at the subgroup meeting on 12 February (whole day). There was no general agreement across INB in the subgroup on the design elements. At the closure of the meeting, the subgroup decided to continue dialogue at the subgroup meetings during INB8.

To strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness and response, the proposed multilateral PABS system should achieve the two objectives of:

Rapid, systematic and timely access to pathogens and GSD, which contributes to

strengthened global surveillance and risk assessment, and facilitates R&D,

innovation and development of health products; and

On an equal footing, equitable, fair and rapid sharing of monetary and non-

monetary benefits from the use of pathogens and GSD, including timely, effective and predictable access to health products, based on public health risks and needs.

In order to meet the objectives, the system should be consistent with the objectives of the CBD and Nagoya Protocol; provide legal certainty; have the maximum possible participation; and be simple, practicable, and transparent. All Parties will contribute to strengthening and sustaining relevant capacities for the effective operation of the PABS System, towards the global public good and global health security.

Key elements of PABS design

1. PABS coverage

Recognising Member States’ sovereign rights over genetic resources, and mindful of the importance of ensuring access to human pathogens for public health preparedness and response purposes, the PABS System will cover biological materials1 and genetic sequence data (GSD) for pathogens with pandemic potential2.

2. Access

2.1 Upon becoming aware of pathogens with pandemic potential within its territory, each Party will, using applicable biosafety, biosecurity and data protection standards:

2.1.1 Immediately share with WHO any sequence information known to the Party;3 and

2.1.2 As soon as biological materials are available, provide the materials to one or more laboratory/ies and/or biorepository/ies participating in WHO- Coordinated Lab Networks (CLNs) (any relevant WHO-coordinated laboratory alliances or networks per established ToR and modalities for technical collaboration4); and

2.1.3 As soon as pathogen GSD is available, upload the GSD and relevant metadata to one or more WHO-recommended PABS Sequence Database/s (SDBs) (publicly accessible databases to be recommended by WHO per established modalities for technical collaboration5, with arrangements to promote accountability and transparency, including notification that GSD uploaded is covered by the PABS System with applicable benefit sharing requirements).

2.2 The PABS System will promote the sharing of biological materials and GSD through the CLNs and SDBs. Parties consent to the further transfer and use of materials and GSD provided to the CLNs and SDBs, subject to applicable biosafety, biosecurity and data protection standards, modalities for technical collaboration and the benefit sharing requirements below. Intellectual property rights may not be sought on biological materials and GSD provided to the CLNs and SDBs.

3. Benefit sharing

3.1 Manufacturers (including those under licensing agreements) commercially producing vaccines, therapeutic or diagnostic products for pathogens with pandemic potential will provide:

3.1.1 Annual monetary contributions, of an amount based on the size and nature of the manufacturer, to support the PABS system and strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness and response capacities in countries in line with Articles 19 and 20; and

3.1.2 In kind contributions, based on the size and nature of the manufacturer, such as capacity- strengthening activities, arrangements for transfer of technology and know-how in line with Article 11, and/or scientific and research collaborations; and

3.1.3 During a PHEIC or a pandemic,6 real time contributions of relevant diagnostics, therapeutics and/or vaccines (X% free of charge and X% at not- for-profit prices), to be made available upon request by WHO and delivered, through the mechanisms set out in Article 13, for equitable allocation on the basis of public health risk, need and demand.

These contributions will be set out in legally binding standard PABS contracts.

3.2 Those who use shared biological materials and GSD for commercial purposes that are not manufacturers will be expected to consider voluntary contributions to support management and implementation of the PABS System.

3.3 Those who use shared biological materials and GSD for non-commercial purposes will be required to appropriately acknowledge, in presentations and publications, the laboratories/Parties providing biological materials and GSD; and expected, as appropriate, to actively engage in scientific and academic collaborations, training and capacity strengthening activities, contribute to public dissemination and transparency of research results, and consider voluntary contributions to support management and implementation of the PABS System.

3.4 Additional to relevant diagnostics, therapeutics and/or vaccines provided by manufacturers as set out above, during a pandemic or a PHEIC, Parties in a position to do so will make relevant products available for equitable allocation on the basis of public health risk, need and demand.7

3.5 All Parties will benefit from strengthened surveillance, risk assessment, and early warning information, services, coordination and cooperation.

4. Implementation and governance

4.1 Implementation of the PABS System will begin when the WHO CA+ is adopted. The access and benefit sharing provisions will come into full effect simultaneously when the WHO DG, in consultation with the PABS Advisory Committee (an independent committee of recognised experts reflecting regional representation, gender balance, and balanced representation between developed and developing countries) determines that the CLNs and SDBs are ready as outlined in sections 2.1.2 and 2.1.3, and the coverage of legally binding standard PABS contracts as outlined in section 3.1 is sufficient to ensure large-scale and continuous benefit sharing. The PABS System is intended as a specialized international access and benefit-sharing instrument within the meaning of Article 4.4 of the Nagoya Protocol, and the Parties will implement it as such at the domestic level through the necessary legislative, administrative or policy measures.

4.2 The Parties will cooperate and take appropriate measures to encourage and facilitate as many manufacturers as possible to enter into standard PABS contracts as early as possible, and to encourage and facilitate benefit sharing through other means until a standard contract is signed, such as conditions in public procurements or on public financing of research and development, prepurchase agreements, regulatory procedures or other appropriate measures.

4.3 The Parties will cooperate to support the effective operation of the PABS System, including by taking all necessary steps to facilitate the sharing of biological materials, and the export of necessary health products during a PHEIC or pandemic8, in accordance with applicable international law

4.4 The governing body will oversee the implementation of the PABS System, and will regularly review its operation, performance, relevance and effectiveness. The WHO DG, supported by the PABS Advisory Committee, will report regularly to the governing body for this purpose.

1 Possible definition of biological materials (as used for WHO Bio Hub): clinical samples, specimens, isolates, and cultures, either original or processed, of a pathogen.

2 Possible definition of pathogen with pandemic potential: any pathogen that has been identified to infect a human and that is: novel (not yet characterised); or known (including a variant of a known pathogen), potentially highly transmissible and/or highly virulent and could cause a PHEIC. (Note: need to consider further in relation to ongoing discussions in the WGIHR and INB on defining a pandemic or pandemic emergency as well as early action alerts).

3 Note: need to consider in relation to IHR Article 6 and related discussions.

4 Regulations for study and scientific groups, collaborating institutions and other mechanisms for collaboration (https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/pdf_files/BD_49th- en.pdf#page=170).

5 Regulations for study and scientific groups, collaborating institutions and other mechanisms for collaboration (https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/pdf_files/BD_49th- en.pdf#page=170).

6 Note: need to consider further in relation to ongoing discussions on defining a pandemic or pandemic emergency as well as early action alerts.

7 Note: need to consider further in relation to ongoing discussions on defining a pandemic or pandemic emergency as well as early action alerts.

8 Note: need to consider further in relation to ongoing discussions on defining a pandemic or pandemic emergency as well as early action alerts.

The Global North

Big Pharma’s position is often stated by Thomas B. Cueni, who served for many years as Secretary-General of Interpharma, the association of pharmaceutical research companies in Switzerland and is now the Director-General of the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA).

He has written a number of articles HERE.

Most would agree that the primary task of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body (INB), established by the World Health Assembly (WHA) in December 2021 to negotiate the draft agreement, is to address the inequities observed in the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, medicines, diagnostics and other countermeasures to low- and middle income Countries (LMICs).

Solutions being proposed by the INB negotiators must undeniably put equity front and centre.

As INB negotiators discuss a Pathogen Access Benefit-Sharing (PABS) System as part of an overall Pandemic Agreement, it is critical to preserve the innovation system and research incentives that were so successful in the fight against COVID-19 and supported the rapid development of vaccines, treatments and tests at record speed and unprecedented scale. Failing to do so will mean we do not effectively tackle the biggest shortcoming of the COVID-19 pandemic – the inequitable rollout of medical countermeasures.

It is essential that provisions of the pandemic accord regarding access to pathogens and genetic sequences provide a decoupled solution, with no strings attached. During the COVID-19 pandemic, access to pathogens and genetic data was swift and unconditional.

Unimpeded sharing of SARS-CoV-2 pathogen data enabled the development of a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine within a record 326 days from the release of the virus’ genetic sequence. Without this principle, private sector engagement will be disincentivized and the measures will prove counterproductive.

Creating a “closed system” that centralizes pathogen access under one organization’s control, as some parties have proposed, would introduce considerable bureaucratic hurdles and could require years, if not decades, to implement.

Stringent requirements for sharing or accessing pathogen data would also severely hinder responses to future pandemics and basic research and development (R&D).

Moreover, pathogens or their genetic sequences aren’t “owned” by any single country; they quickly traverse borders. The idea of incentivizing or paying royalties to countries for spreading dangerous pathogens is outright absurd.

The private sector must be involved, and we must avoid overlaps, whereby manufacturers willing to sign up to the public-private partnerships created by the Pandemic Accord would be exposed to benefit sharing obligations and to national Nagoya ABS provisions.

To be practicable, the partnership should reach a critical mass to come into force – the idea of coercing companies to engage is unrealistic.

Another issue is that the current draft text introduces very problematic clauses on mandatory contributions to finance the PABS… and any concept of “annual monetary contributions based on size and nature of the manufacturer” essentially amounts to a corporate tax.

The Biden administration and the pharmaceutical industry are… united in an effort to block developing countries from access to U.S. firms’ patented information on vaccines and drugs when the next pandemic hits.

U.S. negotiators working on a global treaty that aims to guide the world’s response whenever a new deadly pathogen emerges have rejected proposals to loosen patent protections, a step that could enable developing countries to quickly make their own versions of the vaccines and drugs.

For those countries and their advocates, it’s a striking stance — given what happened after Covid arrived: They shared data about new variants only to see the rich world hoard most of the vaccines.

“There’s a contradiction, [an] enormous amount of hypocrisy,” said James Love, director of Knowledge Ecology International, who advocates for wider access to health products, of the Biden administration’s position.

The State Department declined a request to interview the chief U.S. negotiator, Pamela Hamamoto.

Unlike Medicare price negotiations, pharma views the erosion of intellectual property rights as an existential threat to its business model, said Lawrence Gostin, faculty director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University. He has advised the White House and the World Health Organization, the U.N. body that convened the pandemic treaty negotiations.

“The Biden administration is willing to push the envelope, but they’re not willing to break the business model,” Gostin said.

WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus warned this month that nations’ unwillingness to compromise means they might miss the May deadline to finalize the treaty.

“We will have missed our chance to make history,” Tedros said at a meeting with member countries. This would be a “missed opportunity for which future generations may not forgive us,” he added.

More than a dozen senators from both parties, including Chris Coons (D-Del.) and Mike Crapo (R-Idaho), wrote to Biden and Tai this month asking them to reject the waiver of patent protections for tests and treatments because, they said, it wouldn’t improve global access to Covid drugs while negatively impacting “American manufacturers, innovation, and global competitiveness.”

“The United States believes strongly in Intellectual Property (IP) protections, which serve to fuel investment and innovations,” she said.

Nearly 20 House Democrats signed a similar letter in December.

Pharma representatives said that forcing them to share their formulas wouldn’t lead to much manufacturing in the developing world because companies seeking to produce vaccines and drugs need knowledge and expertise that don’t come with patents.

“This doesn’t work if it’s coerced,” said Thomas Cueni, director general of the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations, of the patent waivers.

And the Biden administration… has taken pharma’s side in the treaty negotiations that could guide the world’s response to the next pandemic. Some European nations, including Germany, have also sided with their drugmakers.

The top U.S. negotiator for the pandemic treaty, Hamamoto, argued in a meeting in Geneva in November that requiring more access to U.S. drugmakers’ inventions would undermine the very system that worked in response to Covid without improving access during future pandemics.

“The United States believes strongly in IP protections, which serve to fuel investment and innovations,” she said.

“The countries sharing the viruses, the pathogens, are not doing us a favor,” Cueni of the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations, said. He explained that all countries have a keen interest in the development of treatments that combat disease.

THE GLOBAL SOUTH

I have written about this before…

The U.S. wants “all the sharing of technology, or removing IP barriers or financing, to be on voluntary basis and mutual agreement, which means leaving the world to be under the will of pharmaceutical companies and rich countries,” said Mohga Kamal-Yanni, senior global health policy adviser at the People’s Vaccine Alliance, a coalition of more than 100 organizations that advocates for unfettered access to shots.

Representatives of developing countries have made similar points during the talks.

“For the future, why would we be hesitating [and] have no workable measures” given the Covid experience, wondered Mohammad Kamruzzaman, a Bangladeshi diplomat.

Bangladesh is part of a group of 29 countries from Africa, Asia and Latin America promoting the developing world’s position in the negotiations.

They argue that they should be compensated for providing pathogen data that drugmakers use to develop vaccines and drugs.

“What we don’t want is that we agree right now to very strict obligations in terms of prevention and surveillance, and then all that we want — the benefit-sharing, the flexibilities in intellectual property, the funding — all that remains open to be discussed in the future,” said one diplomat from a middle-income country granted anonymity to speak candidly.

Meanwhile, progressives, whom Biden needs on his side to win reelection this November, continue to pressure the administration.

“We are working with the administration and their representatives to the World Health Organization to make sure that they stand up to the drug companies, and that they make sure, in a variety of ways, that [through] the production of generic drugs, information sharing, etc., that all people on this planet are able to get what they need in terms of vaccines,” said Sen. Bernie Sanders, the Vermont independent who’s the faction’s champion.

The detailed position of the Third World Network:

WHO: Attempts to side-line Africa and Equity Group proposal on the PABS System

18 February, Geneva (TWN) – Proposed design elements for the Pandemic Access and Benefit Sharing (PABS) System disregard key features of the comprehensive PABS proposal which has garnered support from at least 72 developing countries.

The Vice-Chair and Co-Facilitators of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body (INB) on a new pandemic instrument jointly drafted the proposed design elements for the PABS system. These proposed design elements undermine the efforts of developing countries to lock in concrete mechanisms that will operationalise equity during a public health emergency/pandemic.

The document titled “Article 12: Proposed Design Elements for PABS by the Vice Chair and Co-Facilitators” dated 7 February drew heavily from the European Union's access and benefit sharing (ABS) proposal disseminated in late December 2023.

This is contrary to the understanding that the INB Bureau/Subgroups will generally support the text or elements having cross regional support. The Africa Group proposal has the backing from Member States in Asia and Latin America. It is not clear whether the EU’s proposal enjoys any support from other developed countries or regions.

The document was discussed on 12 February in a hybrid meeting at the WHO headquarters in Geneva.

The document states: “… proposed design elements were discussed in informal consultations and two subgroup meetings on 31 January and 1 February 2024. This version was revised based on comments and suggestions from the two subgroup meetings. It will be reviewed and discussed at a further subgroup meeting on 12 February (whole day)”.

It further states, “After the 12 February subgroup meeting, it is envisaged that if there is general agreement on the design elements, the Vice-Chair and Co-Facilitators, with support from the WHO Secretariat, will prepare proposed text for negotiation by the INB drafting group”.

A delegate told TWN that despite several developing countries highlighting the inadequacy of the proposed elements as the basis for a PABS system in the subgroup meetings, their concerns were brushed off.

Another developing country delegate said the meeting on Monday (12 February) was about “getting a buy-in for the elements proposed by the Vice-Chair and Co-Facilitators which are based on the EU’s ABS proposal with the involvement of EU stakeholders as ‘experts’. During the meeting, the Vice-Chair invited these specific EU stakeholders as ‘experts’ to clarify and remove ‘misunderstandings’ that the Global South supposedly carries”.

Handpicked Stakeholders as Experts

Interestingly the WHO Secretariat handpicked certain “stakeholders” as “experts” to participate and make presentations during the full-day subgroup meeting on 12 February. For example, Amber Hartman Scholz, the Head of Science Policy and Internationalization Department of Leibniz-Institut DSMZ German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, and Guy Cochrane, Team Leader, Data Coordination and Archiving, EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute were invited.

Both have stakes in the questions discussed on 12 February 2024. They are part of a network known as DSI Network funded by Germany, several members of which have been consistently arguing against altering the current system of sharing of genetic sequence data (GSD) which lacks accountability and transparency leading to inequitable extraction of data in a manner inconsistent with open science.

These experts did not have any interest in addressing the concerns of developing countries.

Proposals of developing countries sidelined

The Vice-Chair and Co-Facilitators’ design elements undermined proposals of developing countries. For example, the PABS proposal of the Africa Group/Group of Equity suggests the creation of a WHO PABS Sequence Database – a database that will facilitate access for all users including all databases and be accountable to WHO and its Member States.

According to developing country delegates, in the informal meetings during the first week of February, the WHO Secretariat categorically ruled out having such a database in the WHO, arguing that they had no capacity and that it would be a costly affair. Requests from developing countries to the WHO Secretariat for it to provide information on capacities that would be required and potential costs for such an initiative so that an informed decision may be made, have been ignored. The WHO Secretariat declared in the subgroup meeting that “it has no plans to establish a database”, compromising the proposal made by the Africa Group and Group of Equity.

According to a developing delegate, “This proposed new WHO database does not mean the other existing databases cannot function or other new databases cannot be established. On the other hand, it would set up a standard for fair, open and accountable sharing of GSD of pathogens that would guarantee open access and increase benefit sharing.”

Taking a cue from the WHO Secretariat, the Vice-Chair of the subgroup said to developing countries that their proposal was neither realistic nor implementable.

The WHO Secretariat’s adamant position, echoed by the Vice-Chair, left many developing countries surprised and frustrated. Neither should be taking unilateral decisions or sides during these discussions. Instead, their role should be to assist Member States by furnishing requested information, and facilitating discussions among Members so that an informed decision can be taken by WHO Members.

The design elements of the PABS as proposed in the Vice-Chair and Co-facilitators’ text for the 12 February meeting says that States Parties will upload GSD into “publicly accessible databases to be recommended by WHO per established modalities for technical collaboration, with arrangements to promote accountability and transparency, including notification that GSD uploaded is covered by the PABS System with applicable benefit sharing requirements”.

The phrase “per established modalities for technical collaboration” is qualified with a footnote which refers to “Regulations for study and scientific groups, collaborating institutions and other mechanisms for collaboration” of WHO.

The document lacks detail on what would be the “modalities for technical collaboration”, and specifically how accountability to WHO Members and transparency will be achieved. It is also unclear who will determine these modalities; will it be the WHO Secretariat or Member States? The proposed sketchy approach bears the risk that the modalities will not be acceptable to developing countries that fear inequitable extraction of data; or by databases, thereby hindering the sharing of data. In this context, the developing countries’ proposed WHO PABS Sequence Database is perhaps more sensible.

The proposed PABS design elements also suggest a similar approach for the sharing of physical materials, i.e. it is suggested that pathogen samples and other related materials be shared through "one or more laboratory/ies and/or biorepository/ies participating in WHO-Coordinated Lab Networks (CLNs) (any relevant WHO-coordinated laboratory alliances or networks per established terms of reference and modalities for technical collaboration)”. Here again the term of reference and Technical Modalities are linked to a footnote referring to “Regulations for study and scientific groups, collaborating institutions and other mechanisms for collaboration”, in the Basic Documents of the WHO.

Nothing in the proposed elements explains the terms of reference and modalities for technical collaboration, its contents and how they will be set out. No clarity is provided on which laboratory/ies and/or biorepository/ies will form part of the CLNs.

These elements again sideline suggestions from the Africa Group and Group of Equity, which have proposed that any sharing of materials with the proposed WHO-designated Laboratories Network should be subject to binding terms and conditions to avoid misappropriation of shared materials. Such an approach is followed by the WHO’s own Pandemic Influenza Preparedness (PIP) Framework whereby the sharing of biological material for influenza virus of pandemic potential is subject to a standard material transfer agreement (known as “SMTA 1”). The Africa Group and Group of Equity have also called on Member States to agree on what specifically will be part of the WHO-designated laboratory to ensure fairness in terms of representation and capacity.

“It is clear from the WHO Secretariat’s attitude towards developing country proposals in INB and WGIHR (Working Group on the Amendments to the International Health Regulations 2005) and it will be increasingly difficult for us to entrust them to set these terms and conditions. We simply don’t know what falls under their classification of “technical modalities”, according to a developing country delegate.

Interestingly, while the WHO Secretariat snubbed developing countries’ call for binding terms and condition, modelled on SMTA 1 in the PIP Framework, it insisted on following the monetary and non-monetary benefit-sharing approach of the PIP Framework, again side-lining the Africa Group/Group of Equity proposal on how to approach monetary benefit sharing.

In its design elements, the Vice-Chair and Co-facilitators proposed setting a ceiling limit for monetary benefit sharing and a menu of in-kind contributions as non-monetary benefit sharing options.

According to sources familiar with the INB discussions, the Vice-Chair and the WHO Secretariat linked monetary benefit-sharing from the PABS system to the resources needed for the implementation of the PABS system, using that as a basis to determine the ceiling for monetary contributions. Developing countries’ proposal for payment of “x” percentage of the total revenue generated using shared resources under the PABS by any user monetarily gaining from the system, was not reflected in the design elements.

Some delegates said that the Vice-Chair and WHO Secretariat were antagonistic towards this proposal, which they believe was not given due consideration.

Developed countries argued that monetary contribution should not just be for the implementation of the PABS system but also the implementation of other provisions of the pandemic instrument.

A developing country delegate said that monetary contribution should also support the implementation of international health regulations as such.

On in-kind contributions, the Vice-Chairs and WHO Secretariat insist on a “menu” of activities “such as capacity-strengthening activities, arrangements for transfer of technology and know-how in line with Article 11, and/or scientific and research collaborations” for PABS users to choose from. The elements suggest (though it should be confirmed) that this menu would be in addition to reserving a percentage of the supply of relevant diagnostics, therapeutics and/or vaccines free of charge and at not-for-profit prices.

The Africa Group/Group of Equity have proposed very specific in-kind contributions (manufacturing licenses for developing country manufacturers, affordable prices for all developing countries and compliance with WHO’s allocation mechanism, if available) to be provided during a PHEIC and pandemic, to provide legal certainty of sufficient supplies at affordable prices for developing countries. Their proposal also addresses access needs of developing countries including for WHO stockpile prior to a PHEIC. This proposal of specific in-kind contributions of the Groups was also disregarded.

On 14 February, the Vice-Chair and Co-Facilitators reissued the same proposed PABS design elements. Key elements from the Africa Group/Group of Equity continue to be conspicuously absent. This document notes “[t]here was no general agreement across INB in the subgroup on the design elements. At the closure of the meeting, the subgroup decided to continue dialogue at the subgroup meetings during INB8”.

An analysis by Sangeeta Shashikant

As Geneva was winding down for the Christmas break last December, the European Union (EU) circulated a six-page proposal on access and benefit-sharing to World Health Organization (WHO) Members. The proposal comes at a very late stage of the negotiations on the pandemic instrument and is expected to spark significant concerns.

The EU proposal, which deviates from international norms established by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and its Nagoya Protocol is expected to exacerbate inequity, discourage the timely sharing of specimens and sequences by WHO Members, undermine national sovereignty, and erode the intergovernmental character of the WHO. The multilateral benefit sharing proposed by the EU is wholly inadequate and terribly flawed.

This critique examines in detail the critical aspects that underscore the deficiencies in the EU's proposal and its possible ramifications on international collaboration during public health emergencies.

Inconsistency with Rights of State Parties under the CBD and Nagoya Protocol

The access and benefit-sharing link and rights are rooted in historical injustice; entities in developed countries misappropriating genetic resources from the Global South, claiming monopoly rights via the intellectual property system, and failing to share benefits arising from the use of the resource concerned. The term “biopiracy” was popularised, that shaped the negotiations of the CBD’s third objective of fair and equitable benefit sharing.

Consequently, in 1992 with the adoption of the CBD, it was internationally accepted that States have “sovereign rights” over their biological resources, a principle also accepted by WHO Members in the context of the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Framework (PIP Framework). Accordingly, the CBD (and subsequently its Nagoya Protocol) dictates that access to genetic resources shall be contingent upon prior informed consent of the country providing the genetic resources and fair, equitable benefit-sharing on mutually agreed terms (operationalised through legally binding contracts).

According to Article 4(4) of the Nagoya Protocol, these elements can be multi-lateralised through a “specialised international instrument” (SII), provided that such instruments “are supportive of and do not run counter to the objectives of the Convention and this Protocol”.

Unfortunately, the EU's proposal falls short of meeting this established legal standard. Paragraph 5(e) of the proposal asserts that access to samples and sequence data is to be granted “without conditions” “to requesting recipients” (defined as an “institution, organization or entity”), contradicting the core principles of the CBD and its Nagoya Protocol.

Paragraph 5(d) of the EU’s proposal mentions “guidelines” to be developed by the WHO Secretariat, but these are only for recognition of laboratories and biorepositories as well as databases capable of receiving samples and sequence data. Guidelines are by their very nature non-binding and have in the past failed to deliver equitable outcomes.

Moreover, the EU proposes for the guidelines to be set out by WHO along with other Quadripartite Organisations for One Health Approach (World Organization on Animal Health, FAO and UNEP). This effectively means that the guidelines will be prepared by the secretariats of these organisations and there will be very little Member State scrutiny over the development of the said guidelines. The Quadripartite has been called out for ignoring access and benefit-sharing regimes in their draft joint plan of action for implementation of the One Health Approach.

These discrepancies not only make a mockery of the international rights vested in State Parties (which the EU is also legally obligated to uphold) but also raises concerns about the proposal's potential to exacerbate inequities and consequently discourage the timely sharing of samples and sequence data. In essence, by diverging from established international norms, the EU proposal threatens to impede the collaborative spirit required for effective health emergency/pandemic preparedness and response.

Separately, of concern is the central involvement of the Quadripartitite in the development of guidelines including “guidance on the interpretation on what constitutes an unknown pathogen” in paragraph 3, and thus what the Quadripartitite expects WHO Members to rapidly share with the proposed WHO Pandemic Access and Benefit Sharing System (PABS), and the Quadripartitite’s role in coordinating the network of WHO laboratories. This is worrisome from the perspective of the implications for national sovereignty of WHO Members and their authority in making decisions within the WHO.

Undermining the intergovernmental character of WHO & Proliferation of Conflicts of Interests

The WHO operates as an intergovernmental organization answerable to its Member States, which hold decision-making authority. Nevertheless, the EU proposal blatantly disregards the decision-making role of WHO Members by suggesting in paragraph 2 that the PABS system shall be administered by a multi-stakeholder partnership made up of “the WHO, and the relevant organisations of the UN system, other relevant international organisations, regional organisations and stakeholders, including civil society and the private sector.” This partnership will determine the details of the benefit-sharing contracts, enter into agreements with the manufacturers of health-related products and is also tasked with operationalising the availability and affordability of supply during a pandemic/public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC).

In addition, extremely worrying is that the EU proposal will perpetuate conflicts of interests. The private sector, with whom benefit-sharing contracts are to be signed and from whom supply is required, would now be in a position to influence the various elements of the PABS system. Further, the central role given to the private sector in capacity building of scientists from developing countries as well as WHO-coordinated laboratory network in the context of benefit sharing (see below) is very disturbing because the provisions have the potential to undermine the trust in public health laboratory systems and science in developing countries.

A multi-stakeholder approach to governing PABS is unnecessary and undesirable. COVID-19 has highlighted the failure of the “multi-stakeholder” approach as the Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT)-accelerator proved inadequate. An effective PABS system depends on a governance mechanism that is independent, free of conflicts of interests and accountable to WHO Members, a pathway successfully followed by the PIP Framework.

Scope of “Pathogens” Beyond Health Emergencies & Pandemics

The EU’s proposal obligates the sharing of all viruses or organisms “that cause(s), or can cause a disease to its human host”. This extends to any existing or new viruses/organisms as well as any variants. The proposed scope is unjustifiably broad, extending far beyond pathogens that cause health emergencies and pandemics.

According to a long-time observer of the CBD process, this proposal might be part of a larger policy of the EU to undermine other national and multilateral ABS regimes etc., by expanding access to genetic resources while minimizing benefits to be shared.

Further, the EU proposal requires not only the sharing of the physical sample of pathogens but also “epidemiological and clinical information useful for its utilisation”, within a strict and specific timeframe.

If agreed, the EU proposal will require WHO Members to set up country-wide surveillance infrastructure encompassing all organisms that have even the slightest possibility of causing disease in humans and to share all such biological resources and related epidemiological and clinical information with a global network of laboratories, without any conditions and with a dysfunctional benefit sharing mechanism.

No Binding Conditions Attached to Access: Repeating Failures of the Past

Prior to the adoption of the PIP Framework, WHO-designated laboratories receiving influenza samples of pandemic potential were governed by WHO guidelines, which the receiving laboratories, such as the WHO Collaborating Centres, repeatedly violated.

As it emerged, non-compliance and misappropriation of shared samples and sequences (as such laboratories filed extensive patent claims) was rife among WHO-designated laboratories; trust in the flu virus sharing system eroded, with developing countries insisting on revamping the system. These calls grew louder as affected developing countries also struggled to obtain timely affordable access to vaccines at the height of the H5N1 avian flu outbreak and H1N1 pandemic.

In 2011, WHO Members unanimously adopted the PIP Framework, which provides a framework for international cooperation with respect to global influenza surveillance and response with two legally binding standard material transfer agreements (SMTA). SMTA 1 governs sharing among WHO-designated laboratories (i.e. national influenza centres, WHO Collaborating Centres, H5Reference labs, Essential regulatory laboratories), and SMTA 2 governs sharing with entities outside of such laboratories.

The PIP Framework also contains Guiding Principles for the development of Terms of Reference (TOR) for the respective category of WHO-designated laboratory, as well as the TORs, which set out the parameters of the technical work that such laboratories will undertake. SMTA 1 thus legally requires receiving laboratories to comply with the respective TOR. It is noteworthy that the terms and conditions of access and use by WHO-designated laboratories and other entities were determined by WHO Members and not the WHO Secretariat.

The success of the PIP Framework is widely known. In 2016 a WHO expert review group considered the PIP Framework as a “bold and innovative tool for pandemic influenza preparedness.” The benefits it generated were even handy for several countries during the COVID-19 pandemic response. The role of PIP benefits is well documented.

In view of this background, the EU proposal takes many steps backwards. Instead of building on the successful PIP Framework model, the EU is opting for a failed approach that is also inconsistent with international norms and an effective global framework.

EU Recognizes Multilateral Benefit Sharing, but it is Distorted and Grossly Inadequate

On the surface, the EU proposal appears to propose a detailed benefit-sharing mechanism. However, the devil is in the details. Multilateral benefit sharing is proposed in two parts in paragraph 6, with “part A - specifically during a pandemic situation” and part B - “At all times”.

The EU proposes to include these benefit sharing elements in benefit-sharing contracts that will be developed by the multistakeholder platform (partnership) that includes the private sector and other stakeholders that may also uphold the private sector interests, an evident conflict of interest. The contracts will be made public subject to protecting “commercial confidentiality”, meaning the vital operational aspects of the contracts may never be public.

Under part A (specifically during a pandemic situation), while a pandemic situation persists, manufacturers of pandemic-related health products shall make available to the “partnership … only upon request of the partnership … on a quarterly basis ([...%] free of charge and [...%] at not-for-profit prices) … for distribution on the basis of public health risk, need and demand”.

In times of a pandemic, the worldwide demand for health products, particularly diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines, will exceed available supply. Hence, it is crucial to involve manufacturers across different regions and sub-regions in the production of essential pandemic-related items. The most expeditious approach to broaden production capacity is through licensing, wherein manufacturers are granted the authority to produce and are provided with the necessary technology and know-how. Notably, while this aspect is addressed in the Access and Benefit-Sharing (ABS) proposal put forth by developing countries described below, it is conspicuously absent from the EU text.

Further, the various caveats attached to the EU proposal are likely to result in inequitable access, as experienced during COVID-19. Benefit in part A will only be operationalised on request of the partnership. Involvement of the private sector (and other related stakeholders), as well as developed countries (that would wish to have priority access) in the partnership, has the strong potential to cripple any rapid request for supply to developing countries.

Furthermore, as there is no legal commitment on a manufacturer to supply until a request is made by the partnership, manufacturers will not have reserved any supply for PABS/WHO. In the meantime, manufacturers will have entered into various advance purchase agreements with rich countries, promising priority supply. It could be many months before supply is available for developing countries, even if a request is ever made by the partnership.

Moreover, supply to be provided is also only “on a quarterly basis”, which suggests that the recipient of the supply will be at the back of the queue, while the distribution is to take into account “public health risk, need and demand”. While “public health risk and need” can be determined based on data pertaining to prevalence and its effects, the issue of “demand” is contestable.

For example, extension of the 17 June 2022 TRIPS Decision to diagnostics and therapeutics is being challenged in the WTO by developed countries and multinational pharmaceutical companies on the basis that there is no demand for therapeutics for COVID-19. Developing countries, WHO and civil society have repeatedly countered that the problem is not one of demand but of timely availability and affordability. As a result of this dispute, the WTO has failed to extend the TRIPS Decision within 6 months of its adoption as mandated by the 12th Ministerial Conference. One and a half years later, extension of the WTO TRIPS Decision remains pending, having missed the December 2022 deadline.

In contrast, developing countries’ ABS proposal requires each manufacturer/developer of health products to contractually commit to providing at least 20% of its “real-time production” of each pandemic-related product manufactured to WHO for distribution based on “public health risk and need”. This means that all manufacturers/developers have to legally commit to place supply to the WHO for equitable distribution, with WHO at the top of the queue. Manufacturers entering into advance purchase agreements with other nations would already be aware of their legally binding commitments to ensure adequate supply is available for WHO at all times. Thus, any further agreements would not interfere with supply reserved for equitable distribution.

In part B (at all times), the EU proposes in sub-paragraph (i) that manufacturers “commit to engage in capacity-building and scientific and research collaboration on mutually agreed terms with scientists and researchers from developing countries” with respect to R&D and production of products related to the pathogen sample. This aspect offers nothing more than status quo, for it is “mutually agreed terms” and, as such, voluntary.

In sub-paragraph (ii), the EU suggests that manufacturers of health products will contribute to support the WHO coordinated laboratory network, including capacity building of laboratories and biorepositories from developing countries in the network “and their ability to rapidly detect and characterise pathogens and analyse genetic materials”. For this purpose, “annual contributions” will be set out in the benefit-sharing contracts.

This proposal is self-serving with the pharmaceutical sector and rich countries being the main beneficiary. The pharmaceutical industry will build capacity and provide annual contributions so that developing countries can rapidly share samples and sequence data for the development of pandemic health products, which can be sold for massive profits to rich countries.

While the mention of annual contributions suggests monetary benefit sharing, no detail is provided as to the formula for deriving monetary benefits or the ceiling that will be collected. Alarmingly, the proposal is for the annual contributions to support surveillance and rapid samples/sequence data sharing (the only aspect that interests the pharmaceutical industry and the EU) and not for other preparedness activities, e.g. health system strengthening or response measures during a PHEIC or a pandemic.

This marks a significant departure from the PIP Framework which has a clear benchmark for collecting monetary benefits from influenza vaccines, diagnostic and pharmaceutical manufacturers using the WHO Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System, with agreement among WHO Members that 70% is to be used for preparedness (which is not limited to surveillance) and 30% for pandemic response. A high-level implementation plan is regularly designed by the PIP Secretariat in consultation with the PIP Advisory Group after receiving feedback from various stakeholders, including the private sector and civil society.

Further in part B sub-paragraph (iii), when a PHEIC persists, the EU proposes that “upon request of the Partnership”, the manufacturers shall make available “at not-for profit prices” a certain percentage of the products “on a quarterly basis”, “for use on the basis of public health risk, need and demand”.

“Not for profit” is not defined throughout the EU text. In effect, during a PHEIC, only a certain percentage will be available at an undefined “not for profit” price, implying that the remaining supply will be available at high prices. There is also no certainty of supply due to the various caveats attached to the text.

In addition, the proposal takes a concerning turn by stipulating that, in the scenario where a PHEIC escalates into a pandemic, quantities provided during the initial PHEIC phase will be considered part of the overall supply commitment for the subsequent pandemic phase. This aspect of the proposal reveals a lack of commitment on the part of the EU to realise equitable outcomes, as supply should dynamically scale up to meet the heightened demand during a pandemic, raising serious doubts about the proposal's ability to adapt effectively to the evolving and intensified demands of a widespread health crisis.

Double Standards in Addressing Intellectual Property Concerns

In paragraph 5(h), the EU prohibits intellectual property claims only on pathogens and genetic sequence data in the form received (i.e. the unmodified form). It recognises samples and data may be otherwise subjected to intellectual property and calls for respect for proprietary technology used in the preparation of samples.

The EU's proposed text fosters the potential for misappropriation of shared samples and sequences through the intellectual property (IP) system, contributing to the perpetuation of inequity. Moreover, the text exhibits a disturbing double standard. Despite the stated objective of the pandemic instrument being to enhance production and supply for equitable access, the EU proposal not only advocates for the preservation of existing IP monopolies on technologies but also facilitates the establishment of such monopolies. This stance erects formidable barriers to additional research and development (R&D) as well as production efforts by manufacturers in developing countries, in addition to concerns of misappropriation.

Unreasonable Exemption in EU Proposal

The EU proposal exempts all Not-For-Profit Organisations, who are recipients of the pathogen samples or data from obligations of benefit sharing. It must be noted that a Not-for-Profit Organisation does not necessarily mean that these organisations do not generate revenue. For e.g. universities may use sequences, claim patents over the use for the development of diagnostics and subsequently license the same for royalties. Such entities that generate revenue from the use of the PABS system should contribute to monetary benefit sharing and to license such technologies to developing country manufacturers.

Gaps in the EU Proposal Will Hinder Effectiveness of PABS

Visibly absent from the EU proposal are terms and conditions determined by WHO Members on the sharing and use of genetic sequence data (GSD), an issue of critical importance to developing countries.

Instead, the EU’s proposal requires each party to rapidly share sequences by uploading to databases recognized by WHO. It further absurdly suggests development of guidelines (which have no legal effect) for recognition of databases capable of receiving and transferring sequences, by WHO in consultation with databases that are to be subject to the guidelines. Since WHO Members and their laboratories are sharing GSD, the terms of access and use should be decided by WHO Members and should have legal effect such as being subject to data access agreement, which is already commonly used with respect to GSD of potential pandemic pathogens. Such an approach has been suggested by the developing countries in their ABS proposal, with the terms to be determined by WHO Members.

Another gap can be found in paragraph 7(f)(ii). It states that PABS will only be operational after a certain percentage of manufacturers have concluded benefit-sharing contracts. This poses a challenge for the effectiveness of PABS as other manufacturers that have not signed benefit-sharing contracts will be able to free-ride on the PABS system (receive samples and GSD, as no legally binding conditions apply to access) once it becomes operational, and thereby will not be motivated to sign benefit-sharing contracts, threatening the entire ABS system and equitable access during PHEIC and pandemics.

Overall, the EU proposal is a blatant attempt to transfer vast resources, especially from the Global South (a hotspot of organisms) to the Global North without terms and conditions and meaningful, fair, and equitable benefit sharing.

Developing Countries ABS Proposal Offers Meaningful Equity

72 developing countries – the Africa Group and Group for Equity have proposed a comprehensive PABS system that builds on the PIP Framework model, taking into account the gaps and lessons learned in its operationalisation and the challenges of inequity faced during COVID-19. In view of the vast support of WHO Members behind this proposal, it should be the starting point of negotiations. Notably this proposal does not suffer from the deficiencies and gaps highlighted above.

The Africa Group/Group for Equity proposal introduces standard terms and conditions (SMTA 1) as a necessary element for governing the sharing of PABS samples and sequences among the WHO network of laboratories. It further includes SMTA 2, which is applicable to the transfer of PABS Materials to Recipient Entities, defined as developers or manufacturers of diagnostics, vaccines, therapeutics, and other medical products.

The SMTA 2 also outlines benefit-sharing commitments designed to expedite affordable access to vaccines, diagnostics, therapeutics, and other products to deal with PHEIC and pandemics including by diversifying production through licensing and expanding supply options. The benefit-sharing commitment also includes consideration of addressing developing countries needs, including for WHO stockpile prior to PHEIC, with the aim to prepare for an early response, at the recommendation of the WHO Director-General and complying with WHO’s allocation plan, if such a plan is recommended by WHO.

The Africa Group/Group for Equity proposal also attaches the detailed SMTAs to the text which are missing from the EU paper.

In addition, the 72 developing countries’ maintain that users who derive financial benefits from the PABS system should provide meaningful monetary benefit-sharing contributions to support pandemic preparedness, and response, with details on its operationalization.

With respect to GSD, they propose enabling access through a transparent, multilateral PABS Sequence database accountable to WHO Members that ensures transparency, accountability and importantly operationalizes fair and equitable benefit sharing, with the use of click-wrap data access and use agreements for users wishing access as well as Database Access Agreement between WHO and other databases. Details of these agreements are to be determined by WHO Members.

Below is the Pathogen Access and Benefit Sharing system from the October 30, 2023 version of the Framework Convention (“Pandemic Treaty”). Take it all with the proverbial grain of salt because a new version is due any day.

Article 12. Access and benefit sharing

1. The Parties hereby establish a multilateral system for access and benefit sharing, on an equal footing, the WHO Pathogen Access and Benefit-Sharing System (WHO PABS System), to ensure rapid and timely risk assessment and facilitate rapid and timely development of, and equitable access to, pandemic-related products for pandemic prevention, preparedness and response.

2. The WHO PABS System shall ensure rapid, systematic and timely sharing of WHO PABS Material, as well as, on an equal footing, timely, effective, predictable and equitable access to pandemic-related products, and other benefits, both monetary and non-monetary, based on public health risks and needs, to strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness and response.

3. The Parties shall implement the WHO PABS System:

(a) in a manner to strengthen, expedite and not impede research and innovation;

(b) at all times, both during and between pandemics;

(c) in a manner to ensure mutual complementarity with the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Framework; and

(d) with governance and review mechanisms, to be determined by the Conference of the Parties.

4. The WHO PABS System shall have the following components:

(a) WHO PABS Materials sharing:

(i) Each Party, through its relevant public health authorities and authorized laboratories, shall, in a rapid, systematic and timely manner:

(1) provide WHO PABS Material to a laboratory recognized or designated as part of an established WHO coordinated laboratory network; and

(2) upload the genetic sequence of such WHO PABS Material to one or more publicly accessible database(s) of its choice, provided that the database has put in place an appropriate arrangement in respect of WHO PABS Materials.

(ii) The WHO PABS System shall be consistent with international legal frameworks, notably those for the collection of patient specimens, material and data, and will promote findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable data available to all Parties.

(iii) The Parties shall develop and use a Standard Material Transfer Agreement (a PABS SMTA), which may be concluded through electronic means, and which shall include relevant biosafety and biosecurity rules, to be used with the transfer of WHO PABS Materials from a laboratory recognized or designated as part of an established WHO coordinated laboratory network to any Recipient.

(iv) Recipients of WHO PABS Material shall not seek to obtain any intellectual rights on WHO PABS Material.

(b) PABS multilateral benefit sharing:

(i) Benefits, both monetary and non-monetary, arising from access to WHO PABS Materials, shall be shared fairly and equitably, pursuant to a PABS SMTA, which may be concluded through electronic means.

(ii) The PABS SMTAs shall include, but not be limited to, the following monetary and non-monetary benefit-sharing obligations:

(a) in the event of a pandemic, real-time access by WHO to a minimum of 20% (10% as a donation and 10% at affordable prices to WHO) of the production of safe, efficacious and effective pandemic-related products for distribution based on public health risks and needs, with the understanding that each Party that has manufacturing facilities that produce pandemic-related products in its jurisdiction shall take all necessary steps to facilitate the export of such pandemic-related products, in accordance with timetables to be agreed between WHO and manufacturers; and

(b) on an annual basis, contributions from Recipients, based on their nature and capacity, to the capacity development fund of the sustainable funding mechanism established in Article 20 herein.

(c) The Parties shall also consider additional benefit-sharing options, including:

(i) encouraging manufacturers from developed countries to collaborate with manufacturers from developing countries through WHO initiatives to transfer technology and know-how and strengthen capacities for the timely scale-up of production of pandemic-related products;

(ii) tiered-pricing or other cost-related arrangements, such as no loss/no profit loss arrangements, for purchase of pandemic-related products, that consider the income level of countries; and

(iii) encouraging of laboratories in the WHO coordinated laboratory network to actively seek the participation of scientists from developing countries in scientific projects associated with research on WHO PABS Materials.

5. In the event that pandemic-related products are produced by a manufacturer that does not have a PABS SMTA under the WHO PABS System, it shall be understood that the production of pandemic-related products requiring the use of WHO PABS Materials, implies the use of the WHO PABS System. Accordingly, each Party, in respect of such a manufacturer operating within its jurisdiction, shall take all appropriate steps, in accordance with its relevant laws and circumstances, to require such a manufacturer to provide benefits in accordance with paragraph 4(b)(ii) of this Article.

6. The Parties shall develop a mechanism to ensure the fair and equitable allocation of pandemic-related products, based on public health risks and needs.

7. The Parties shall ensure that all components of the WHO PABS System are operational no later than 31 May 2025. The Parties shall review the operation and functioning of the WHO PABS System every five years.

8. The Parties shall ensure that the WHO PABS System is consistent with, supportive of and does not run counter to the objectives of the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization thereto. The WHO PABS System will provide certainty and legal clarity to the providers and users of WHO PABS Materials. The WHO PABS System shall be recognized as a specialized international access and benefit-sharing instrument within the meaning of paragraph 4 of Article 4 of the Nagoya Protocol.

The United States proposed the following text in April 2023:

[USA PROPOSED ARTICLES]

[Proposed Article A. Multilateral Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness, and Response Benefit Sharing System

1. The Parties agree that the Multilateral Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness, and Response Benefit Sharing System (“the Benefit Sharing System”) is to be established. Furthermore, the Parties agree that the Benefit Sharing System shall be established with the voluntary participation of relevant stakeholders, including participants of health partnerships, the private sector, civil society, and international organizations, on terms to be determined by Member States. The Parties emphasize that the role of relevant stakeholders in the development of this system is to be prioritized immediately.

2. The Parties affirm that both the benefits and the Benefit Sharing System are intended to be used to support more rapid, effective, and equitable pandemic prevention, preparedness and response based on public health needs, including, inter alia, health emergency workforce, populations most at-risk for severe illness or death, and responses in complex humanitarian crisis settings.

3. The Parties intend for the Benefit Sharing System to:

a. be efficient, feasible, practical, and effective;

b. generate more benefits, including both monetary and non-monetary, than costs;

c. be implementable during and between pandemic emergencies;

d. provide certainty and legal clarity for providers and users of biological materials and genetic sequence data from pathogens with pandemic potential;

e. strengthen, expedite, and not impede research and innovation;

f. be consistent with open access to genetic sequence data (GSD) and related metadata from pathogens with pandemic potential;

g. incorporate practices to ensure biosafety and biosecurity; and

h. be implemented in a manner consistent with applicable national and international laws, regulations, and other obligations.

4. The Parties intend for the Benefit Sharing System to perform the following functions:

a. provide, where appropriate, surveillance, risk assessment, and early warning information and related services to all countries with regard to pathogens with pandemic potential;

b. provide, where appropriate, capacity building in surveillance, risk assessment, and early warning information and related services to the Parties with regard to pathogens with pandemic potential;

c. Facilitate, where appropriate, the safe and secure conduct of basic, applied, translational and clinical research regarding pathogens with pandemic potential;

d. prioritize during a pandemic emergency, rapid and equitable access to safe and effective diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines against pathogens with human pandemic potential, particularly to populations of concern affected by the pandemic emergency, according to public health risk and needs and particularly where those countries do not have their own capacity to produce or access vaccines, diagnostics, and pharmaceuticals;

e. build capacity in countries over time, in particular for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with the voluntary participation of relevant stakeholders and commensurate with the country capabilities, including through: technical assistance; regulatory strengthening; transfer of technology, skills, and know-how on voluntary and mutually agreed terms; and geographically distributed manufacturing and supply chains, tailored to the country’s public health risk and needs.

5. The Parties recognize that the WHO CA+ conveys numerous benefits, which the Parties consider to be benefits also conveyed by the Benefit Sharing System to be established in accordance with Article X, Section/Paragraph 1. These benefits, as identified in the WHO CA+, may include but are not limited to the following:

a. sharing of biological materials, GSD and related metadata from pathogens with pandemic potential;

b. transparency and coordination on global supply chains for pandemic emergency response-related products, including with the voluntary participation of relevant stakeholders;

c. national measures that promote timely and equitable access to pandemic emergency response- related products during a pandemic emergency based on public health risks and needs, including through provisions in publicly funded purchase agreements and the use of pooled procurement mechanisms for pandemic emergency response-related products;

d. support for building and strengthening capacities, based on need, mutual agreement, and as appropriate. Such capacity building could include, inter alia:

i. core capacity requirements for surveillance and response, as outlined in Annex 1 of the International Health Regulations (2005);

ii. regulatory systems;

iii. biosafety, biosecurity, and biorisk management;

iv. basic, applied, translational, and clinical research;

v. health emergency workforce development; vi. manufacturing of pandemic emergency response-related products, including regionally distributed manufacturing, tailored to public health risk and need and considering the capacity of the Party for long-term sustainable funding

e. coordination, collaboration, and cooperation in scientific research and responserelated activities;

f. licensing and technology transfer for pandemic emergency response-related products on voluntary and mutually agreed terms;

g. related bilateral, regional, or global capacity building and technical support and assistance;

h. support for establishing and maintaining regional stockpiles of pandemic emergency response- related products and products for other health emergencies;

i. financing for pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response; and j. sharing of research results.

6. The Parties recognize that contributions of monetary and non-monetary benefits to be shared by relevant stakeholders shall be considered as part of the Benefit Sharing System.

7. In part to support the Benefit Sharing System, the Parties intend to urge, direct the WHO to urge, and request other relevant global partners to urge, manufacturers of pandemic emergency response-related products to:

a. set aside a portion of each production cycle of these products for procurement by/for LMICs;

b. implement tiered pricing for these products, based on income level of countries;

c. engage rapidly with any relevant global, regional, or other access mechanisms, including those that provide these products to LMICs;

d. at the earliest opportunity, develop, publish, and implement global access plans that are designed to facilitate timely and equitable global access to their products, and include provisions in purchase agreements that further these goals;

e. support WHO in strengthening regulatory (prequalification and Emergency Use Listing) capacities and in supporting in-country activities that promote reliance on these authorizations during health emergencies; and

f. support financing for strengthening pandemic preparedness and IHR core capacities.

8. In part to support the Benefit Sharing System, the Parties intend to urge nongovernmental entities, global health actors, and regional entities that procure pandemic emergency related response products, including personal protective equipment, to include provisions that facilitate timely and equitable global access to those products in those entities’ purchase agreements.

9. The Parties agree the WHO CA+ in its entirety shall function, in conjunction with the International Health Regulations (2005), and contributions of relevant stakeholders to support pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response, as a specialized international instrument[s] for access and benefit sharing for human and zoonotic pathogens. USA]

[USA Proposed Article B. Sample and Data Sharing

1. The Parties recognize the need for rapid and transparent sharing of biological materials1 , including samples of human and potential zoonotic pathogens, particularly those with epidemic and pandemic potential, as well as genetic sequence data (GSD) and relevant metadata from human and potential zoonotic pathogens, as a key component of pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response.

2. The Parties also recognize that the distribution of genetic sequence data and the practices of biological material and genetic sequence data sharing require appropriately designed solutions for facilitating access and for benefit sharing to prepare for and respond to health emergencies.

Access to human and potential zoonotic pathogens

3. The Parties, through their national health authorities, shall share, in a rapid and timely manner, biological material with established laboratory networks, laboratories, and biorepositories,

subject to applicable national and international laws, regulations, rules, and standards, including relating to biosafety, biosecurity, and transport, and consistent with relevant national and international frameworks for collection of patient specimens and epidemiological data.

4. The Parties intend to share biological material pursuant to paragraph 3 in accordance with the following:

a. Access to biological material is accorded expeditiously and free of charge, or, when a fee is charged, it does not exceed the minimal cost involved;